For investors, having trust in their portfolio to deliver the expected returns is more important than aiming for higher profits. Yet, higher risk is sometimes welcome if it is well rewarded and understood. The first few months of the global pandemic were clearly not one of those times. The uncertainty drove up the premium paid by higher-risk assets classes.

According to the 2019 Global Competitiveness Index by World Economic Forum (WEF), almost 95% of the GDP of GCC economies operate with substantially better financial markets than the entire MEA region. The GCC region also runs better institutions, assessed on transparency and property rights, across more than 85% of its GDP. Globally, Saudi scored in the top-10 in the key dimensions of corporate governance, financial stability, and speed in adapting the legal framework to digital business models. The UAE is in the top-10 for public-sector performance, future orientation of government, and entrepreneurial culture. To top the score on the check list of an international investor, the GCC overall has almost 95% of GDP operating at the highest level of macro-economic stability in the world.

Despite the fluctuating oil prices, the GCC has been weathering the storm comparatively well, showing a solid framework for investors to operate in. Thanks to its strong fiscal and external balance sheets, and comparatively low public debt level, rating agencies provided a positive and stable outlook for Saudi Arabia despite dwindling cash reserves. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the UAE to have 3.5% drop of GDP this year to be followed by a 3.3% growth in 2021, bringing a sense of urgency to investors to refresh their 2021 pipeline. Other oil dependent GCC countries may need to navigate uncertainty for longer, yet remain in a privileged position compared to many advanced economies. This provides a good backdrop to attract and reassure jittery investors, with one target standing out. In recent years, GCC countries have unswervingly focused on localization to create jobs, infrastructure, and new technologies: A clear platform for investors.

COVID-19 has sparked a debate on the viability of global supply chains, with regional footprints on the rise. This could be the dawn of localization as a everyone’s favorite. Yet, COVID-19 is one of the last crises in a series. The 2008 financial crisis almost brought global economic activities to a grinding halt through lack of liquidity in capital markets. In 2011, the tsunami that hit Japan wreaked havoc on physical assets and caused sustained shutdowns that affected supply chains worldwide. Since 2018, ongoing trade wars have severely affected global commerce creating a push toward shorter value chains driven by protectionist policies. Investors have to look at their options through the lens of unpredictable disruptions, striking a balance with profitability.

We conducted a research on how the current localization plan of ten industrial sectors handled the extreme test of the last 13 years. This study measured the sensitivity of key enablers of business, and derived recommendations that guide an investor.

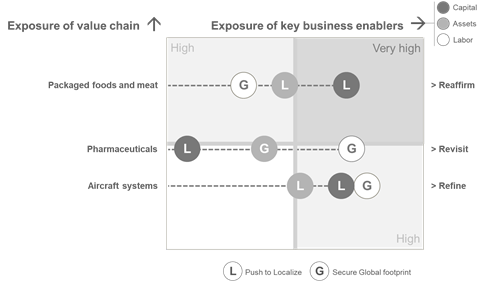

The study found that sectors heavily dependent on operating capital should be kept close to their national banks, as localization can act as their big ticket out of a financial crisis. By contrast, sectors with high labor intensity need to balance localization with a global footprint; for example, when most of Europe was going into deep lockdown, China was beginning to reopen and despite the speed at which the contagion was spreading, there were at least two months between regional peaks. Once further analyses accounted also for the effects of asset intensity and long value chains, the study found a composite landscape, where sectors are pulled in contrasting directions.

Despite the complexity, the solution becomes clear: the best way for investors to move forward is to look at localization by considering one of three potential outcomes for each industry:

- to reaffirm the existing intent to localize;

- to refine current thinking in light of the potential impact of disruption;

- to revisit the case for a more global approach.

The case for localization can be reaffirmed for the following six sectors – industrial machinery, construction materials, metals, consumer electronics, household appliances, and packaged foods and meats. Going local is the best approach and can make the business more robust.

The aircraft and desalination sectors show conflicting reactions to stress, with the latter benefitting from local redundancies, i.e. multiple sites, which may challenge profitability. Their case for localization needs to be refined, accounting for disruptions.

Finally, medical equipment and pharmaceuticals the best way forward is to revisit their case, carefully orchestrating a global value chain to complement a regional footprint. With both sectors a crucial focus for continued investment, and the topic of healthcare security gaining importance, this suggests there may be limits to where localization makes sense or is vitally necessary.

History tells us that disruptions are to be expected, yet they always catch us by surprise. Though future crises are a given, governments and investors can’t afford to assume businesses to not be impacted, or that the current cases for localization will weather all of the frequent storms. In any case, there is a clear imperative to go back to the drawing board and reexamine business in the current climate.